Tracing my roots in China (寻根) - Part I: Fujian and Xu Jia Chong

One month ago, I touched down on a gray, rainy day in Shanghai Pudong International Airport. It was my first time in China in five years, and I felt a mix of emotions — excitement, joy, worry, and confusion.

I was born in China, and immigrated to the US when I was 2.5. Growing up in a predominately white part of Southern California, I had a strong urge to assimilate — to fit in, and to stand out from Asian stereotypes. Instead of homecooked Chinese food, I wanted McDonalds. Instead of Saturday Chinese School, I wanted to watch Saturday morning cartoons.

A few years ago, I realized I had some shame around being Chinese American, and began the journey to openness & curiosity about my ethnic identity. This year, I co-organized events including Lunar New Year and Duan Wu Jie, and built community with friends who are part of the Chinese diaspora. Each event felt deeply healing and meaningful — now, I had the chance to trace my roots to their source.

2023 is a confusing time to return to China as a Chinese American. At a macro level, US-China relations have soured through COVID as Xi Jinping tightens his grip on power, and the US has started to decouple from China economically with the CHIPS Act. China’s economy is worsening. Having just visited Taiwan and discovered long-lost family there, I felt stressed about heightened tensions across the Taiwan Strait with a critical January 2024 Taiwan presidential election upcoming.

On the taxi ride from Pudong to my hotel, my head was swimming in big questions: What is modern China like? How much of what western media is portraying about China right now is true vs. false? What is Chinese culture and what are its roots? What are my roots?

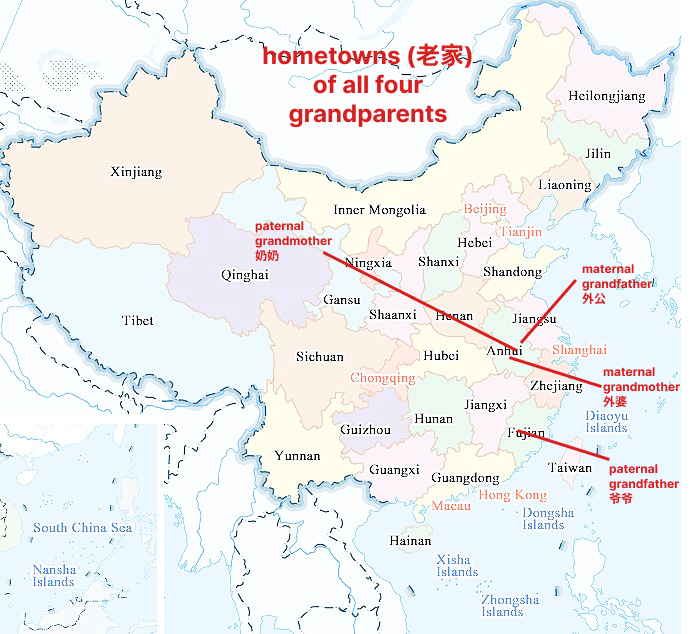

First and most importantly, I wanted to spend quality time with my three surviving grandparents, all of whom are in their 80s, and my aunts, uncles, and cousins. Second, I planned to visit the ancestral homes of all four grandparents and trace my roots back as far as I could. Finally, I wanted to get a sense of modern China as best I could, especially youth unemployment and the economy. This post will focus on the second — tracing my ancestral roots.

Guilin, Dehua County, Fujian - 爷爷 (paternal grandfather)

My last name is Lai (赖),which takes after my paternal grandfather Lai Chong Min (赖重民), who was born in 1938, the third of five siblings — two older sisters, and two younger brothers. Lai Chong Min Ye Ye was born in Guilin, in Dehua County in Fujian province.

Fujian is the coastal province of China closest to Taiwan, known for its mountainous terrain and culture of seafaring immigration (Taiwan is 73.3% Fujianese, and the Chinese restaurants in the US on the East Coast are overwhelmingly Fujianese). Dehua County is known for its porcelain ceramics, especially its all white porcelain treasured during the Ming and Qing dynasties.

Growing up, my grandfather was intelligent and studious. In the first few years of his life, Japan occupied China during WWII; luckily the Japanese army didn’t penetrate mountainous and remote Dehua. In 1949, when the communists defeated the nationalists in the civil war, my grandfather was 11. The whole town heard on the radio that the communist People’s Liberation Army (PLA) was approaching. My grandfather and several of his friends were so scared they hid underneath a stove, where firewood would normally be placed. They only came out when they realized the PLA didn’t harm civilians. At 16, my grandfather left to go to a boarding high school in a neighboring town; because of the shoddy roads and no money to pay for a bus he walked for three full days to get there. He later went to Anhui for university in the capital of Hefei, was sent to the countryside as part of Mao’s efforts to educate the poor and later became a high school math teacher in 泾县, where I was born. His salary was a measly 30 Chinese renmenbi a month (today he gets a pension payment of thousands of renmenbi a month), and before he had kids he sent 1/3 of it home every month to support his ailing mother. He spent the next 30 years in 泾县 as a math teacher and assistant principal until his retirement in 1998.

I asked my grandfather about how the Great Leap Forward and Cultural Revolution affected him. He said that he was in university at the time of the Great Leap so was largely unaffected, and because his class background was modest (farmers and small business owners) and his occupation as a teacher was respected, his family escaped the wrath of the red guards.

When my dad, my uncle, and I took the high speed rail to Fujian, we were greeted by my grandfather’s little brothers (his middle brother a farmer, and his younger brother a doctor), their children, and the children of his now deceased two older sisters. I was immediately struck by the dialect my relatives spoke, which I didn’t understand a word of. Though they also spoke Mandarin (普通话), they primarily spoke to each other in southern Min / Hokkien (闽南话), which is the same dialect as Taiwanese.

Together, we drove up a windy mountainous pass to visit the grave of my grandfather’s father, my great grandfather, who was born in 1909, just two years before the end of the Qing Dynasty and the beginning of the Republic of China. We did a beautiful ancestor veneration ritual — cleaned my great grandfather’s grave, wielded a calligraphy brush to repaint the engraving in red, and burned joss paper for him to use in the afterlife. The air was alive with the smell of smoke, and the boom of fireworks. Then, three generations together bowed three times in unison as my grandfather’s youngest brother led us in words of veneration. I felt deeply moved.

Afterwards, we drove down the mountain to an intricate ancestral temple — our 宗祠 (Zong Ci). I learned that everyone in the whole area was named Lai (赖) — I was blown away by this. In fact, the entire surrounding area, which now contains mostly a few thousand farmers, who care for the various ancestral temples, are all named Lai (赖).

“How long has our Lai family been here?” I asked.

“Only a few hundred years” said my uncle. Some 3,000 years ago (~150 generations ago), the original Lai (赖) family originated from Henan province in the fertile yellow river valley basin, the cradle of chinese civilization, and went south to mountainous Fujian. In the west, Christianity and Islam created third spaces, churches. In China, the big family (大家庭) was the religion. I learned that members of the family paid dues to maintain the temple, almost like home owner associations. In modern cities, which are agglomerations of opportunity, people organize by affinity, and by proximity (neighbors), but rarely do we organize by ancestry (blood). I flashed back to an earlier human era, when we grew up in hunter-gatherer tribes of 20-40 where most were blood relatives of some kind or another.

That night, our small Lai clan gathered for a banquet filled with toasts, and rituals. Seeing smiling faces circling around local food and rice wine shots, I felt a unique pang of belonging I had never felt before with these distant relatives who I was meeting for the first time ever.

Xu Jia Chong, Xuancheng County, Anhui - 外公 (maternal grandfather)

A few days later, we drove to Xu Jia Chong, Xuancheng, Anhui, the hometown of my maternal grandfather.

Xu Jia means “family with the last name 徐“ (my maternal grandfather’s last name) and Anhui is the province my mother, father, and I were all born in. My grandfather’s ancestral home was only a twenty minute car ride from our birthplace of Jingxian (泾县)。

My maternal grandfather, Xu Zhi Zhong (徐执中) was born in 1935 as the youngest of 11 children, to a landlord family. He passed in 2012 at age 77 of pancreatic cancer. Born to wealth, he was small, bright, and scholarly. The 徐家 was a massive home with compound after compound filled with airy patios, courtyards, and homes for all members of the extended family. To visit friends, my grandfather was carried around on a tentpole with four people; a laborer carried him to school on his back. At home, he had private tutors who taught calligraphy, Chinese classics, and history. At 15, he was arranged to be married and become the man of the household, but he disobeyed because he wanted to study, so he left home and went to college to study to become a teacher.

The communist revolution in 1949 completely turned his family’s life upside down. In 1950, Mao initiated land reform, and the government seized the land of all landowners, and tore down the Xu Jia’s massive house. During that time, laborers were given the power to physically beat and report their former landlords (in Marxist terms, oppressors); violence and chaos ensued. I was surprised to hear that because of how well my grandfather’s family treated them, laborers protected my grandfather’s family. They said “even though we worked for her [my grandfather’s mother], she always sat at the same table to eat with us.” I felt deeply proud to hear this story.

A few years later, in the Great Leap Forward, and in the ensuing famine, my grandfather’s family had to resort to eating bark on trees, and my grandfather’s father, his father’s two siblings, and many of his own siblings died of starvation. It shocks me to hear that despite his negative class background coming from a landlord class, my grandfather later became a teacher, a precocious young principal, and then one of the five powerful local government officials in 泾县。One night during the Cultural Revolution, word got out that the red guards were coming for him; at the time my now deceased big aunt was 4, and my mom was only 2. My grandfather escaped with my mother during the night to a nearby mountainous village with family, where they hid for over a month until the worst of the violence subsided.

Growing up in the US, both sets of grandparents alternated spending time with us. I have vivid memories of my maternal grandfather as a gentle, benevolent man who grew vegetables in our backyard in Southern California. He enjoyed deep conversations, and every afternoon when I got back from school he would ask: “有没有新鲜事儿“ which translates to “anything interesting to share today?” These questions sparked my curiosity. He patiently taught me Chinese chess, and had a lifelong love of animals. Every night after dinner, we would curl up together on the couch and watch Animal Planet together.

It’s surreal to imagine my grandfather was once the heir to a great mansion, fields of crops, and whole streets of shops, destined to live a life of comfort & culture. Unlike in Fujian, the communist land reform completely destroyed any ancestral temple. Instead, when we visited Xu Jia Chong only a few shoddy houses and crop fields remained, along with a couple of uneducated farmer relatives that we brought gifts for. I feel sadness and regret I’ll never be able to ask him more about his story. Xu Zhi Zhong Ye Ye* - may you rest in peace.

Part II of this piece will include my two other trips - to Hou An and to Mao Ling to my grandmother’s hometowns.

*technically in Chinese, you call your maternal grandparents Wai Gong (外公)and Wai Po (外婆). However, because we were so close growing up we always called our maternal grandparents Ye Ye (爷爷) and Nai Nai (奶奶) too.