4 learnings from managing 100 early childhood educators

Over the past five years, I have employed close to 100 early childhood educators across California and Arizona at my venture backed education company Tinycare.

Tinycare operates a network of micro-schools with 4-6 children per school.

In San Francisco, we provide subsidized housing for early educators, employ them, and then open 4-6 person Montessori inspired schools in their living rooms; in Phoenix, Arizona we run micro-centers in small commercial retail spaces.

one of our ~20 San Francisco Tinycare micro-schools

Here are four things I learned working with so many early childhood educators.

1/ Early childhood educators care deeply about their specific children; not about abstract notions of impact for all children

Last week, I took four of our teachers out to dinner. I asked about their lives, and we small talked about the latest TV shows and weekend brunch spots. Pretty quickly, though, we got to their kids.

Our teachers teared up talking about how much they love their children — how this child is learning to walk; that one’s vocabulary is exploding. They attend their children’s birthday parties years after they graduate from their classrooms.

The mindset of a teacher is very different from that of an analytical tech person. Whereas tech leaders focus on broad, scaled impact rooted in a utilitarian perspective, I have never once met a teacher who thought about abstract “impact.”

Being a teacher means caring immensely about relationships with the specific children & families you are serving.

2/ Experience doesn’t correlate with being a great early educator

In early 2021, we ran a correlation on parent survey data with a number of teacher metrics — including experience — across ten micro-schools. Surprisingly, there was 0 correlation between years of teacher experience and parent NPS.*

One of our star teachers was a 22 year old who moved from Kansas City to San Francisco. She had a community college degree but didn’t finish her bachelors degree, and before that had worked for years as a part-time summer camp counselor. We found she was phenomenal with kids, communicating with families, and was a positive cultural champion. We quickly promoted her.

By contrast, we found that almost all of our most culturally problematic teachers were highly experienced early childhood educators who had worked in center based classroom settings for a decade or more and some had master’s degrees.

Instead of experience or education, what matters are soft skills — psychological security, love for children, communication skills, patience.

The fact that experience doesn’t correlate with quality is promising for solving the 100k+ early childhood teacher shortage. Imagine building training academies that taking Starbucks baristas off the street who love kids and training them into excellent early childhood educators.

*to be clear, we didn’t run this on child outcomes, data of which is famously hard to come by in early childhood.

3/ High trauma leads to cultural challenges and potential for changing lives

Average pay for early childhood educators is barely above minimum wage, and a staggering 53% of early educators are on public assistance. With high rates of poverty, you would expect that incidents of trauma are high, but I was not prepared to face this reality firsthand.

One day, at an all team event, I asked a room of 30 of our teachers to go around and share why they did this work. One of them said “when I’m with the kids, I can provide the love I never received.” The whole room held their breath. A deep truth resonated throughout the room.

Having previously worked only in a tech startup culture, I struggled to manage teachers with high rates of trauma and mental health challenges.

One of my first teachers was diagnosed with bipolar two. Another had what I now understand might be borderline personality disorder. A third I caught lying multiple times.

In all hands settings, certain teachers who were very triggered could dominate the conversation, often in an intensely negative direction. It took me a long time to figure out how to manage this.

And yet, this also meant we could genuinely change lives. I remember one teacher, who shared a single bedroom with her two teenage sons in South Bay with a relative she didn’t have a great relationship with. At Tinycare, we subsidized a 2 bedroom apartment in SF. She sent me a Slack that Tinycare subsidizing her housing was the first time she felt safe sleeping in her own bed for over a year.

Hearing that made all of the challenges worth it.

4/ The future of teacher management is teal

The first year at Tinycare was me, managing our first few teachers. I had no idea what I was doing, especially managing a staff with so much trauma for the first time. When we scaled past the first ten teachers, we needed experienced teacher management.

We hired a superstar center director from Bright Horizons, one of the largest childcare chains in the country. Yet, from day one, the hierarchical management model hit a lot of pushback from our teachers — we heard repeatedly from teachers that they didn’t want to have a manager or 1:1s because they preferred autonomy.

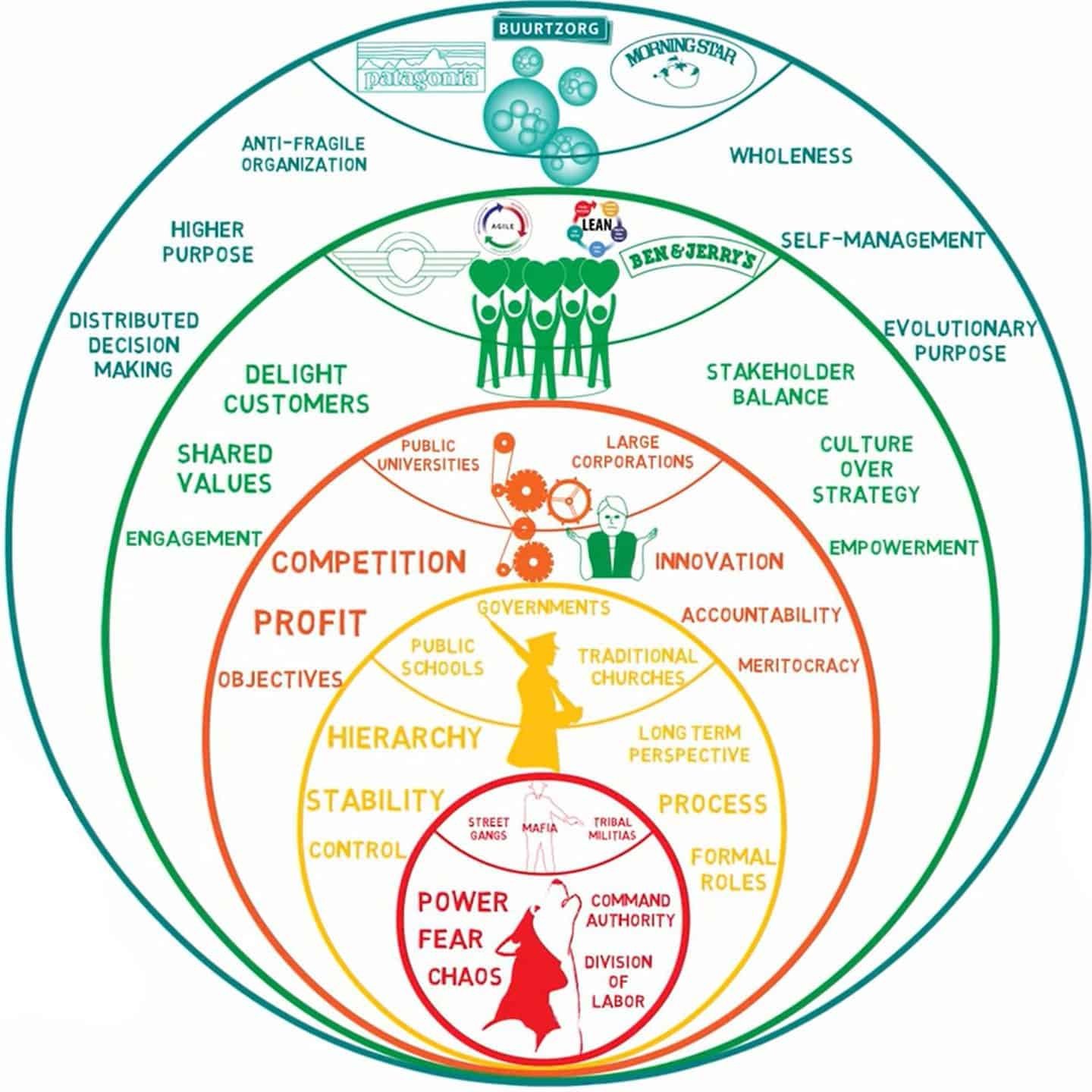

In Reinventing Organizations, Fredrick Laloux writes about an evolution of consciousness in organizations. Currently, most teachers in the country operate in orange organizations — top down hierarchical traditional school models focused on command & control.

Alternative models exist. Buurzorg is a nursing organization with 15,000 nurses organized into self-managing co-operative teams of 8-10 nurses, who make all of the local decisions. The outcomes speak for themselves — Buurtzorg is the fastest growing, best patient outcome, best financially performing, and highest nurse satisfaction nursing org in the Netherlands.

Inspired by Buurtzorg, at Tinycare, after our failed experiment with a top down model in 2021, we designed & launched “villages”, which are communities of teachers led by Mentor Teachers — peer teachers who still teach, and also manage & guide the other teachers for a stipend outside of school hours.

The model of mentor teachers has several benefits: (a) it creates a (b) it creates a pathway from teachers into leadership (c) it’s more affordable for the p&l than full time headquarters staff.

The reception has been incredibly positive. Having run multiple villages at Tinycare for a year, I am bullish for a future that looks less like Bright Horizons, and more like Buurtzorg; a future where teachers can focus on their love for their local community & teams, and still scale within a network that makes broad impact.